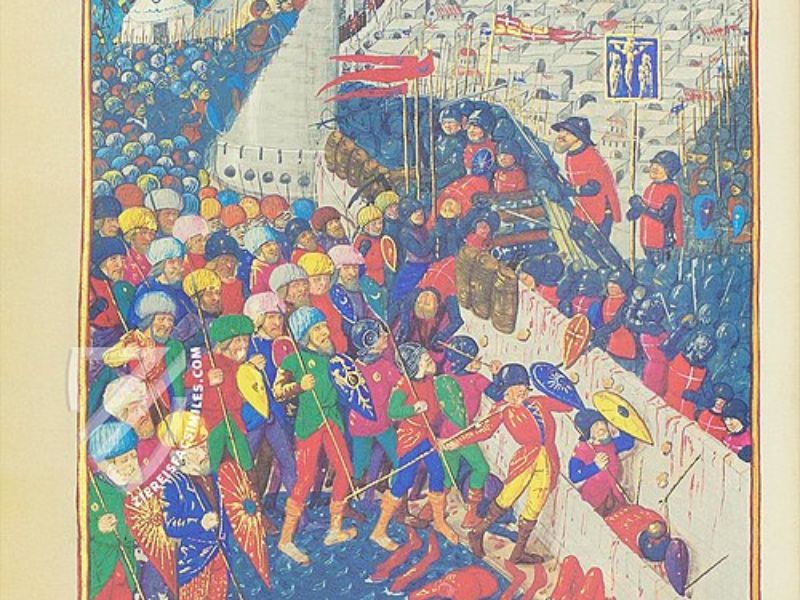

The Last Stand: The Siege of Rhodes in 1522

November 13, 2024

The Great Earthquake of 1856 in Rhodes and the Destruction of the City

November 20, 2024Table of Contents

Introduction

When the Knights of Saint John surrendered Rhodes in 1522, a new chapter began—not only in politics, but in everyday existence. The Ottoman conquest transformed the island’s rhythms, institutions, and social hierarchies.

Yet life in Ottoman Rhodes was not merely a story of domination—it was a complex blend of adaptation, continuity, and quiet negotiation between communities. For nearly four centuries, Muslims, Christians, and Jews coexisted within the walls of the medieval town and its surroundings.

Their daily lives intersected in markets, workshops, and places of worship. While the overarching rule shifted from Catholic chivalry to Islamic imperial order, the people of Rhodes built a new shared normal. Life in Ottoman Rhodes became a mosaic of languages, religions, and traditions layered upon the city’s Byzantine and Hospitaller past.

A New Order in the City

With the Ottoman arrival came administrative transformation. Rhodes was absorbed into the empire as a provincial capital governed by a pasha, with authority over both military and civilian affairs. The Palace of the Grand Master was repurposed for imperial use, while new buildings were added—mosques, schools, and public fountains.

The old Latin elite vanished, and the social structure was reordered. Muslims now held dominant administrative positions, while Christians and Jews fell into defined legal and social categories under the millet system.

Still, the Ottomans maintained many existing practices, recognizing that the success of their rule depended on continuity as much as change. In this blend of control and pragmatism, life in Ottoman Rhodes found its new shape.

Cultural Coexistence and Everyday Interactions

The city’s neighborhoods (mahalles) were often organized along religious lines: Muslim quarters with mosques and hammams, Christian areas with Orthodox churches, and a distinct Jewish district near the port. Yet in daily life, these lines blurred. The marketplace was shared by all, where merchants sold goods in Greek, Turkish, and Ladino.

Water carriers, stonemasons, and tailors of different faiths worked side by side. Religious tolerance was limited but real—protected by imperial law, the Orthodox Church retained its hierarchy, and Jewish communities flourished culturally and economically.

Festivals, family gatherings, and local customs created moments of convergence. Life in Ottoman Rhodes was defined not just by difference, but by interdependence.

Faith, Language, and the Built Environment

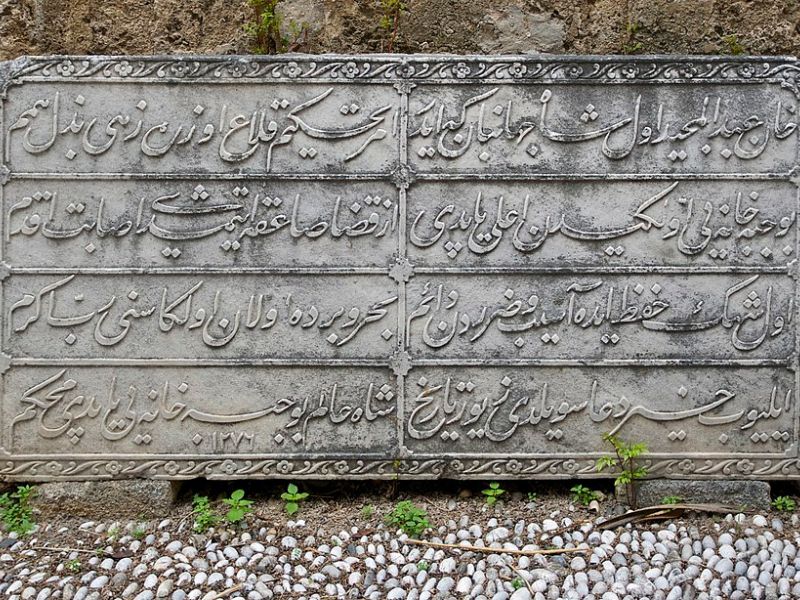

Religious identity shaped not only personal life but also the city’s physical transformation. The Catholic cathedrals of the Knights were converted into mosques—most notably the Church of Saint John, which became the Mosque of Suleiman. New constructions like fountains, madrasas, and bathhouses altered the medieval skyline.

These Ottoman additions did not erase the past, but layered upon it. Language, too, reflected the city’s diversity. Turkish was used in administration, Greek in the Orthodox community, and Ladino among Jews.

The resulting multilingual society required flexibility, and in many cases, residents became fluent in more than one language. Life in Ottoman Rhodes meant navigating a world of plural voices and layered loyalties—one where tradition and transformation walked hand in hand.

Conclusion

Life in Ottoman Rhodes was neither static nor monolithic. It was dynamic, fluid, and shaped by both imperial policies and local resilience. While the Ottoman regime imposed new structures, the soul of the city remained a shared creation. Across the centuries, Rhodes preserved its multicultural essence even as it changed hands and allegiances.

To walk the streets of Rhodes is to see these layers in stone, space, and silence. From the minarets beside churches to the inscriptions in multiple scripts, the Ottoman period left an indelible mark—not only in history books, but in the lived memory of a city shaped by coexistence.

The above article is based on the book ‘Ρόδος’ authored by Theofanis Bogiannos. The article is published with his permission.